- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Tuesday, 22nd November 2016

Another branch of Bartitsu is that in which the feet and hands are both employed, which is an adaptation of boxing and Savate (…) The use of the feet is also done quite differently from the French Savate. This latter … is quite useless as a means of self-defence when done in the way Frenchmen employ it.

– E.W. Barton-Wright, December 1900.

In his articles, interviews and lectures, Bartitsu founder Edward Barton-Wright consistently – and rather cryptically – distinguished the type of kicking taught at the Bartitsu Club from that of French savate, which he disparaged.

This essay offers an interpretation and synthesis of those comments, taking into account their historical, social and technical contexts. If there was a meaningful adaptation or distinction, then what was it and how may it be translated into neo-Bartitsu practice?

Canonical kicks

It may be noted that – although Pierre Vigny was clearly the senior savateur at the Bartitsu Club – Barton-Wright spoke fluent French and had studied savate in its homeland during the 1880s, probably while he was studying at a French university.

The Bartitsu canon, as demonstrated by Barton-Wright and Vigny, however, holds only a very limited arsenal of kicking techniques. The most immediately apparent is a single technique in Barton-Wright’s article series on Self Defence with a Walking Stick:

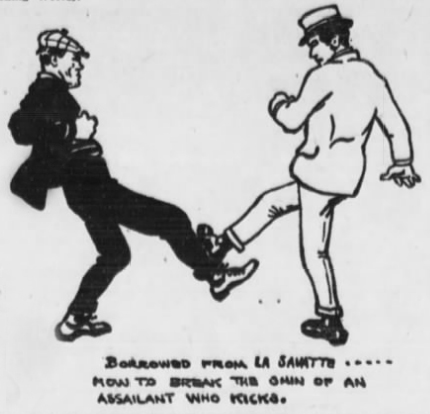

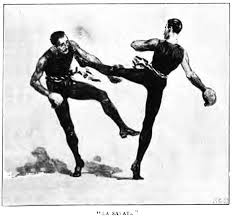

Glossed as “How to Defend Yourself with a Stick against the most Dangerous Kick of an Expert Kicker”, the context for this technique is clearly that of the stick-wielding Bartitsu-trained defender countering a “foreign” ruffian’s stepping side kick. It’s very likely that Barton-Wright and Vigny had in mind the infamous Apache street gangsters of Paris, who were widely known to practice savate.

On this basis, while it can be reasonably inferred that Bartitsu students might train in such kicking techniques well enough to be able to “role play” as Apache savateurs for training purposes, the side kick doesn’t necessarily offer any context clues regarding how a Bartitsu practitioner might kick in self defence.

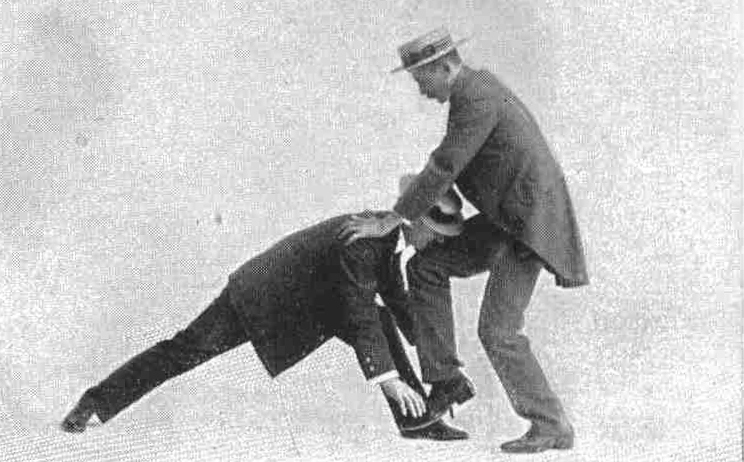

This article series also demonstrates a knee to the face attack, to be performed after the defender has hooked the attacker around the neck with the crook of his cane:

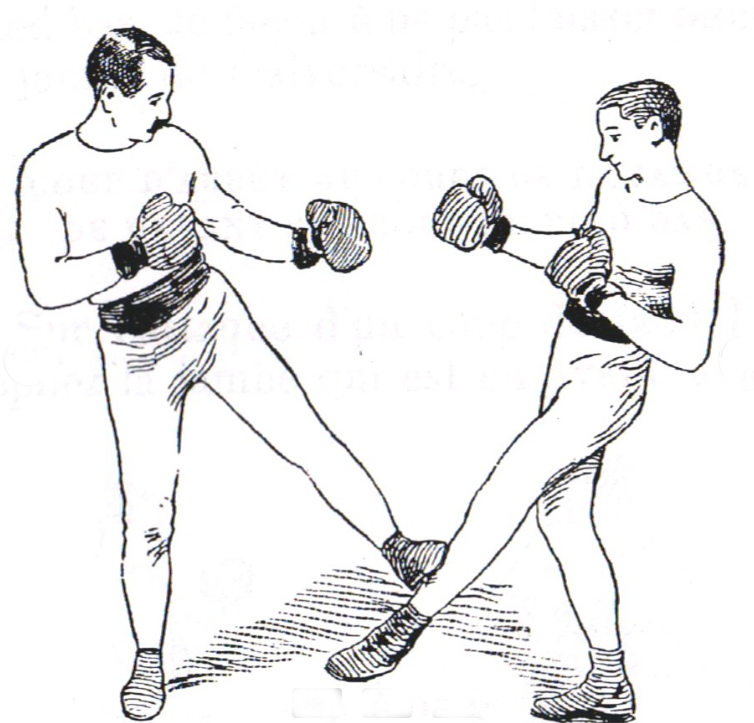

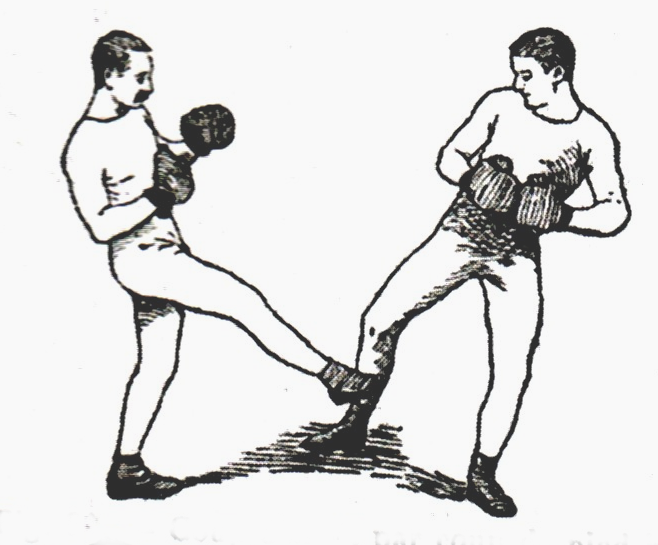

The only other photographic evidence of kicking techniques as part of the Bartitsu canon is this image of Bartitsu Club instructor Pierre Vigny demonstrating a mid-level front or crescent kick as he simultaneously blocks his opponent’s left lead punch and counters with his own left:

A later article in the Pall Mall Gazette also mentioned that the kicking methods taught at the Bartitsu Club were “somewhat different from the accepted French method.”

But how, and why?

The kick felt round the world

For historical context, it’s worth bearing in mind that – on top of the traditional and deep-rooted Anglo-French rivalries – at the time Barton-Wright was introducing his novel concept of Bartitsu to the British public, their most recent impressions of savate had been decidedly negative.

During late 1898, just as Barton-Wright had arrived in London from Japan, the Alhambra music hall had hosted a savate exhibition by French instructor Georges D’armoric and his students. Despite the savateurs’ best efforts and intentions, the reactions of their London audience and critics ranged from grudging appreciation to cat-calling. Although some rural English combat sports did incorporate kicks, kicking was widely held to be brutal and offensive to insular English sensibilities. City-dwellers, in particular, associated kicks with street gangsters rather than with “manly sport”.

Then, during October of 1899, Charles Charlemont had won – under extremely controversial circumstances – a “savate vs. boxing” challenge match in Paris. His opponent had been Jerry Driscoll, a former British navy champion. The British and international sporting press was outraged at the circumstances of that match, decrying the conduct of Charlemont, the referee, the French spectators and organisers and especially at the outcome, in which Charlemont was widely held to have won via an accidental but illegal groin kick.

In this environment, it’s likely that Barton-Wright deliberately de-emphasised the kicking content of Bartitsu and distanced it from the French method as a gesture towards nationalistic sentiment and social respectability. Similarly, he may have been attempting to score points by suggesting that the Bartitsu Club was promoting a “new, improved” (even an Anglicised) version of savate.

Compounding the issue was the fact that savate was, at that time, undergoing a bitter controversy between two factions in its country of origin.

The Academics vs. the Fighters

Although the ultimate cultural origins of savate remain obscure, researchers including Jean Francois Loudcher have traced the art to the working-class custom of “bare-knuckle honour duelling” during the early 19th century. Over the best part of the next hundred years, it evolved in a largely haphazard fashion, played as a rough-and-tumble fighting game in back alleys and cafe cellars, with occasionally successful efforts at codification and systematisation.

By c1900 there was, on one side and in the majority, those who might be characterised as “the academics” – professional instructors, notably including Joseph and Charles Charlemont, who taught and advocated for a stylised, gymnastic form of the art, practiced at least as much as a method of physical culture and artistry as of self defence.

The aim of the academic faction was to firmly establish savate as a “respectable” activity that could be offered to French soldiers and the patrons of middle-class gymnasia, as part of organised physical culture curricula. Due to their influence, the most established and popular version of savate retained the duelling-based tradition of fighting “to the first touch”, translating into a very courteous, light contact combat sport.

It is highly likely that this was the version that Barton-Wright referred to as being “quite useless as a means of self-defence when done in the way Frenchmen employ it.” Much the same thing had been noted by an experienced French observer of the Charlemont/Driscoll fight, who remarked that Charlemont was handicapped by his long experience of “kicking gently” in academic bouts.

The smaller, opposing faction were “the fighters”, represented by Julien Leclerc and others, who preferred an updated, hard-hitting and more pragmatic savate, influenced by the non-nonsense ethos of British and American boxing. The “fighters” represented a counter-culture within the politicised world of fin-de-siecle savate, advocating for rule changes that would push the increasingly genteel art/sport back towards its rowdy, back-alley origins.

Also – and very controversially, at the time – many of the “fighters” were professionals, or at least wanted to have the chance to fight professionally. This caused great indignation among the “academics”, who were largely teachers and proud amateurs and who were horrified by suggestion that their art should be marred by prize-fighting.

The Devil is in the Details

According to the December, 1900 article quoted earlier:

Mr. Barton-Wright does not profess to teach his pupils how to kick each other, but merely to know how to be able to return kicks with interest should one be attacked in this manner.

Interesting but, on the face of it, puzzling; how does one not teach people how to kick each other, but still teach them to return kicks with interest?

The strongest hint yet was given in a September, 1901 interview with the Pall Mall Gazette, in which Barton-Wright reiterated his general theme with the addition of some crucial technical and tactical details:

The fencing and boxing generally taught in schools-of-arms is too academic. Although it trains the eye to a certain extent, it is of little use except as a game played with persons who will observe the rules.

The amateur (boxer) is seldom taught how to hit really hard, which is what you must do in a row. Nor is he protected against the savate, which would certainly be used on him by foreign ruffians, or the cowardly kicks often given by the English Hooligan. A little knowledge of boxing is really rather a disadvantage to (the defender) if his assailant happens to be skilled at it, because (the assailant) will will know exactly how his victim is likely to hit and guard.

So we teach a savate not at all like the French savate, but much more deadly, and which, if properly used, will smash the opponent’s ankle or even his ribs. Even if it be not used, it is very useful in teaching the pupil to keep his feet, which are almost as important in a scrimmage as his head.

… and the interviewer was also given a demonstration of the difference between the savate of the Bartitsu Club and the “accepted French style”, i.e. the style practiced by the majority of French savateurs:

He has also a guard in boxing on which you will hurt your own arm without getting within his distance, while he can kick you on the chin, in the wind, or on the ankle.

As to the usual brutal kick of the London rough, his guard for it (not difficult to learn) will cause the rough to break his own leg, and the harder he kicks the worse it will be for him.

Thus, it’s clear that both Barton-Wright and Pierre Vigny were in the minority “fighters” camp, advocating for a pragmatic, combat-oriented reform of savate that would allow full contact matches and the possibility of knock-outs.

“Come an’ take him orf. I’ve bruk ‘is leg.”

The techniques alluded to include kicks to low, medium and high targets as well as a destructive leg-breaking guard against the “brutal kick of the London rough”, which is possibly cognate with Barton-Wright’s description of “smashing the opponent’s ankle”.

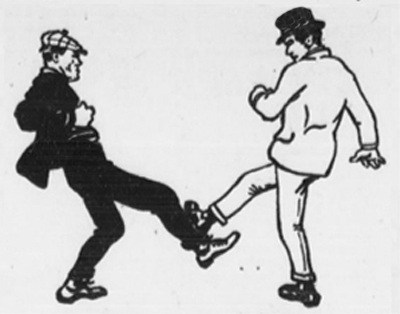

The most famous literary expression of this tactic is certainly the following fight scene from Rudyard Kipling’s In the Matter of a Private (1888), in which Private Simmons launches a vicious kicking attack at Corporal Slane:

Within striking distance, he kicked savagely at Slane’s stomach, but the weedy Corporal knew something of Simmons’s weakness, and knew, too, the deadly guard for that kick. Bowing forward and drawing up his right leg till the heel of the right foot was set some three inches above the inside of the left knee-cap, he met the blow standing on one leg —exactly as Gonds stand when they meditate —and ready for the fall that would follow.

There was an oath, the Corporal fell over to his own left as shinbone met shinbone, and the Private collapsed, his right leg broken an inch above the ankle.

“‘Pity you don’t know that guard, Sim,” said Slane, spitting out the dust as he rose. Then raising his voice—”Come an’ take him orf. I’ve bruk ‘is leg.” This was not strictly true, for the Private had accomplished his own downfall, since it is the special merit of that leg-guard that the harder the kick the greater the kicker’s discomfiture.

Synthesis

Barton-Wright clearly and concisely explained his overall tactical conception of Bartitsu unarmed combat in his February, 1901 lecture for the Japan Society of London:

In order to ensure as far as it was possible immunity against injury in cowardly attacks or quarrels, (one) must understand boxing in order to thoroughly appreciate the danger and rapidity of a well-directed blow, and the particular parts of the body which are scientifically attacked. The same, of course, applies to the use of the foot or the stick …

judo and jiujitsu are not designed as primary means of attack and defence against a boxer or a man who kicks you, but (are) only supposed to be used after coming to close quarters, and in order to get to close quarters, it is absolutely necessary to understand boxing and the use of the foot.

This statement underscores the specifically defensive value of boxing and savate “in order to get to close quarters” against the types of attacks that might be anticipated from a London Hooligan or other ruffian, with the intention of deploying jiujitsu as a type of “secret weapon”. His comments on boxing, like those on kicking, notably emphasise the value of destructive guards that intercept and damage the aggressor’s attacking limbs.

In his article A Few Practical Hints on Self Defence (1900), Percy Longhurst offered a cognate technique, highly reminiscent of that described by Rudyard Kipling:

The English rough can, and does kick, although it is usually after his victim is on the ground; his kicking is barbarous and unscientific. There is, however, one kick that he sometimes uses that is very dangerous, causing terrible internal injuries if not stopped, and it is difficult to avoid if one does not know the counter. It is the running kick at the abdomen.

The defense is to raise the right knee and bring the leg across so that the side of the heel is resting on your left thigh. Your shinbone will catch his leg as it rises at its weakest park, and will probably cause it to break.

As mentioned earlier, savateur Julien Leclerc was another advocate of the “fighters” perspective and, unlike Barton-Wright or Vigny, he left a detailed record of his approach to savate in the form of his book, La Boxe Pratique: Offensive & Defensive – Conseils pour la Combat de la Rue (1903). Leclerc’s manual provided the essential, basic savate kicks detailed in the first volume of the Bartitsu Compendium (2005).

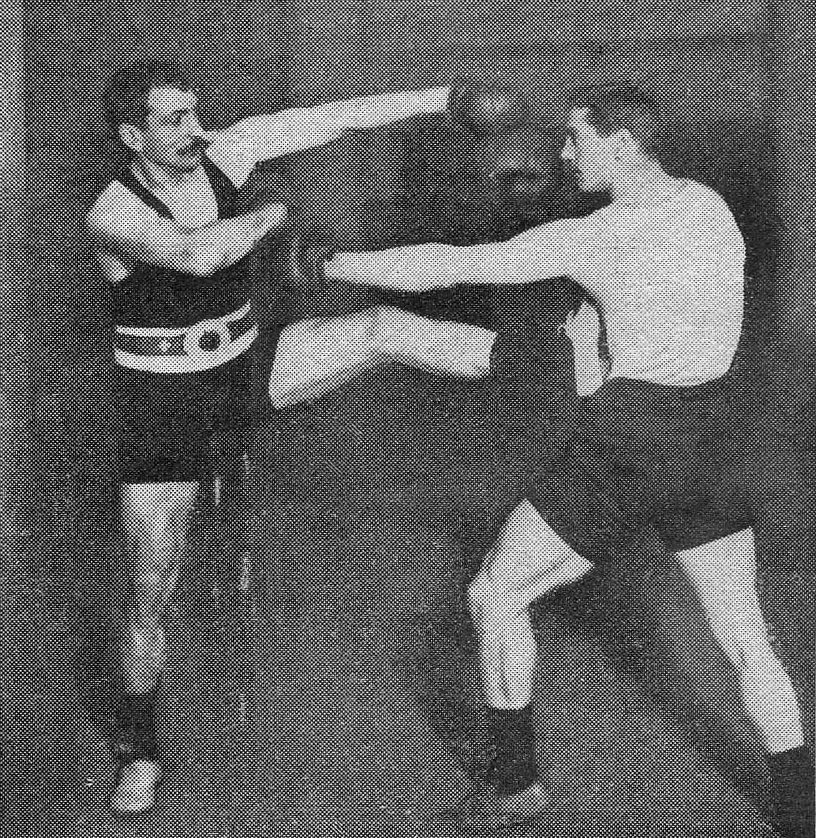

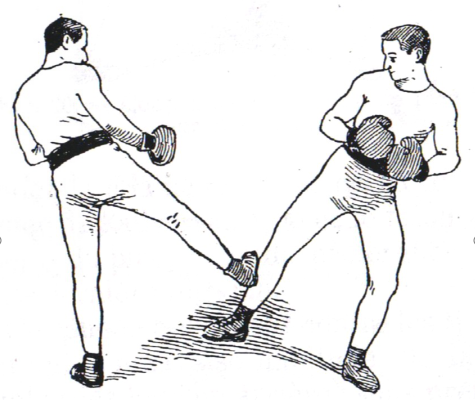

Cross-referencing Barton-Wright’s comments and Vigny’s demonstrations with Leclerc’s manual yields a focus on les coups d’arrets, or “stopping blows”; kicking into kicks, as is shown below:

Thus, the “adaptation” and “distinction” Barton-Wright referred to was, most likely, to hit harder than would be tolerated in the mainstream French salles de savate of his era, and to employ some of the kicks and – especially – counter-kicks of savate toward a Bartitsu-specific tactical goal.

The unarmed or disarmed Bartitsu practitioner should be prepared to counter kicks with hard coups d’arret, chopping into the opponent’s ankles or shins, as part of an aggressive defence strategy. While one might follow with boxing punches, atemi-waza strikes or further kicks as required by the needs of the moment, the tactical aim is to damage the opponent’s limbs and disrupt their balance en route to finishing the fight at close-quarters via jiujitsu – a legitimately “secret weapon” circa 1900, when the Bartitsu Club was the only school in the Western world where a student could study Japanese unarmed combat.

In this video, Bartitsu instructor Alex Kiermayer teaches a set of savate-based low kicks, evasions and stop-kicks: