- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Wednesday, 8th August 2018

Henry Bagge’s article from the February, 1908 issue of Fry’s Magazine strongly echoes the sentiments expressed by E.W. Barton-Wright and other critics of then-contemporary, mainstream French kickboxing.

The theme of “improving” savate (partly via an infusion of English boxing) is ironic in that, during the course of several decades before this article was written, several such infusions had already been made. One of the more recent attempts had, in fact, been carried out at the London Bartitsu Club. Nevertheless, the dominant approach to teaching and practicing savate in France circa 1908 was the stylised, courteous and extremely light-contact style favoured by Charles and Joseph Charlemont.

The Charlemonts’ favored approach was opposed by a minority counter-culture within French kickboxing circles, who advocated for a harder-hitting and more pragmatic style geared towards both prize-fighting and practical self-defence.

Bagge’s subject, savateur Paul Mainguet, was clearly a proponent of the latter school. He recommends employing the evasive and coup d’arret (“stop-hit”) techniques of savate against kicking attacks, plus a small selection of direct, well-proven kicks, relying upon boxing otherwise. Add an emphasis on guards that damage the opponent’s attacking limbs plus the close-quarters grappling of Japanese jiujitsu and you have Bartitsu unarmed combat in a nutshell.

The “kicker” in the accompanying photographs is Georges Dubois, who had, in 1905, famously lost a savate vs. jiuitsu challenge contest against Ernest Regnier, a.k.a. “Re-Nie”. Dubois went on to pioneer a number of interesting “antagonistics” projects, including revivals of gladiatorial combat and Renaissance-era martial arts and creating his own, notably pragmatic, system of self-defence.

La Savate, or French boxing, may be divided into two classes; the first absolutely incorrect, and thoroughly useless as a means of fighting, but distinctly worthy of consideration as a very pretty imitation of the real thing, requiring, as it does, a wonderful display of dexterity, combined with an astounding suppleness of the limbs.

The second, however, is a far more serious business. There is little of the gallery play about it, and as a means of resisting an attack from footpads it is invaluable, and far more deadly in its effects then any blow with the fists.

La Savate, for exhibition purposes, was developed and perfected by Dr. Pengniez, chief surgeon of the Army and hospital, himself a first rate amateur boxer. It was only after a considerable amount of discussion, and repeated consultations with the highest boxing authorities, that the whole thing was reduced to a science, and all the various blows, kicks, and guards consists clearly and concisely tabulated under separate heads.

Undoubtedly the cleverest exponent of la Savate is Professor Mainguet, the world’s middleweight champion of French boxing. In common fairness it should be stated here that M. Bayle, the heavyweight champion, who was to have met Professor Mainguet, and decide once and for all which was the better man, injured his knee so seriously before the match could be pulled off that the question of which of the two is entitled to call himself the world’s all-around champion of la Savate has never yet been decided.

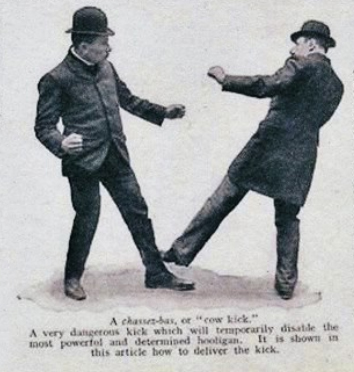

Without wishing in any way to detract from the undoubted skill of M. Bayle, Mainguet’s phenomenal quickness justifies many in the belief that he would have got the decision over his formidable adversary, for it is certain fact that a chassez-bas – a lateral, or “cow” kick on the ankle – will put the strongest man in the world temporarily out of business, and Mainguet can deliver this one kick (among many others, of course) with amazing speed and dexterity.

Mainguet, in addition, is one of the few Frenchmen who are able to differentiate between the English style of boxing and the French, for he has carefully studied the former, and is quite proficient at it. Many French amateur champions have graduated from Mainguet’s school, including Jacques Maingin, heavyweight champion in 1903, and Fry, French lightweight champion of English boxing in the same year. In 1907 he turned out Mazoir, French featherweight champion, both in English and French boxing, carrying off also the 1907 Interschool Challenge Cup for the greatest number of victorious pupils from one school.

It cannot be denied that in real fighting the French method of boxing is absolutely deadly, for no matter how much pluck a man may have, a kick on the ankle, involving, as it does, all the bones and ligaments of the foot, or a stamp on the instep, causes such excruciating pain, and the injured part swells so rapidly, that a man is practically unable to stand on his feet.

It is a curious fact that while the French have so clearly defined what is fair, and unfair, in their fencing schools, and in their duels, they do not seem to have been able to draw a hard and fast line in la Savate; and this is the one great difference between the English and the French styles of boxing.

In the duels with rapiers certain rules are laid down which protect the combatants from all surprises, and the duellist who breaks either of these would be disqualified at once and socially ostracized. But this fairness, which is the basis of the rules which govern dueling, does not appear to regulate the style of fighting used by the lower classes to settle their differences.

Again, in the boxing competitions Frenchmen are absolutely irrational, for, according to the rules which govern la savate, the man who is touched by a slight kick must stop instantly. If, however, the man who is kicked was in the act of rushing, and lands a terrific punch on the jaw after being touched, that punch is declared null and void by the judges.

Eliminating all the spectacular kicks in la savate, there are several which, if carefully studied, would render French boxing so formidable as to be practically invincible, if taken in conjunction with the English style of boxing. It must, however, be clearly understood that the kicks which are described at the end of this article are so dangerous that they are absolutely disallowed in all competitions, and they can only be used very gently when sparring.

Several Frenchmen I have seen box use these kicks only, but they are in the minority, for in France the majority of people go in for English boxing (an imperfect copy of our own), or the classical French boxing, with its puerile conventions.

Some time ago I was discussing with a professor of la Savate the difference between English and French boxing, and I suggested that a judicious blending of the two would make a very formidable mixture, if the man were attacked suddenly in the street. He agreed.

“When I am fighting, “he said, “I strive to forget that I have my feet at all. I only fight with my fists, after the English style as I understand it. I only use the French style to guard the kicks at the instep, and to dodge all the kicks at the lower part of the legs and feet. Then suddenly, while practically in the art of delivering a blow, I land a coup de pied direct (straight jab with the flat of the foot) full in the man’s chest, or un coup de pied de pointe (with the toes of the foot) on the kneecap. If, however, my adversary clinches, I use what is termed a chassez-bas, which smashes one of his ankles, or crushes his toes.

While this may not be very elegant, a man can learn how to do it in one lesson; that is why I teach my pupils English boxing, for I am free to admit that the English method is the only one that is any good. Only a very gifted man can make the great success of the French style of boxing and it is asking a great deal of the ordinary pupil to expect him to have the dexterity of an acrobat.

In my opinion, the best method is the one that the most clumsy man can learn without any trouble, and the beauty of all these easily-learned kicks is that the pupil never forgets them once he has thoroughly mastered them.

The following kicks are considered by the majority of professors of French boxing to be the most dangerous.

Le Chassez-bas

This kick can be delivered with either the left or the right foot, but it is always given as in the chassez-bas with the leg that happens to be foremost at the time. Thus, if a man is boxing in the English fashion; boxing, that is to say, with the left leg and left arm in front, naturally the left leg is the one he uses.

This kick is the only really practical one of the whole lot, and entails no alteration in our usual methods of boxing – of course, always excepting the use of the feet for kicking purposes. The following is the best way of administering this kick –

1. Throw the weight of the body on the right leg.

2. Shorten the left leg, then suddenly shoot it down as if in the act of stamping with the foot crosswise, aiming at the desired spot.

Most vulnerable spots are the following: (1) the toes; (2) the instep; (3) the shinbone; (4) the kneecap.

The man who has been only slightly hurt on any of these spots is very chary of another experience, and wisely keeps at a distance.

The chassez-bas is really very useful, even if only used as a means of defense it makes one’s adversary very uneasy, practically mows down his base, and opens the way to sudden rushes, which, if a man is uneasy, practically take him off his guard.

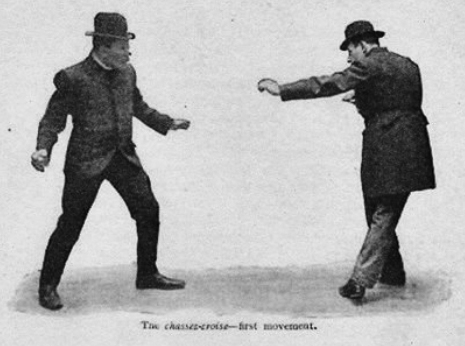

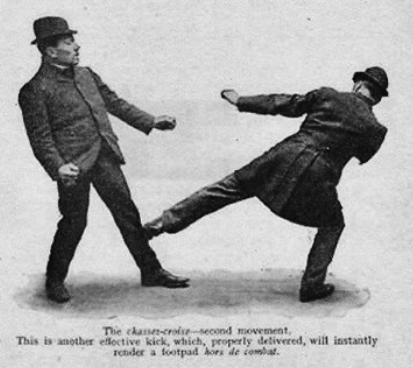

Chassez-croisé

This kick is delivered in exactly the same way as the preceding one, only the one word croisé (to cross), practically explains the act.

Thus, if a man is out of range of his adversary, naturally, as long as he keeps out of the way, he has nothing to fear. If he wishes to still keep at this distance, and yet to deliver an attack, the only way in which this can be done is with the feet, the leg landing on his opponent’s legs. The first thing is to get a little nearer to your adversary; and to deliver the kick effectively the following method should be employed –

Place the point of the right foot beside the outer anklebone of the left foot, draw up the left leg, and strike as in the chassez-bas. If, instead of placing the point of the right foot on the outside of the left ankle, you place it with a jump very much in advance of it, you get all the closer to your adversary to deliver your kick.

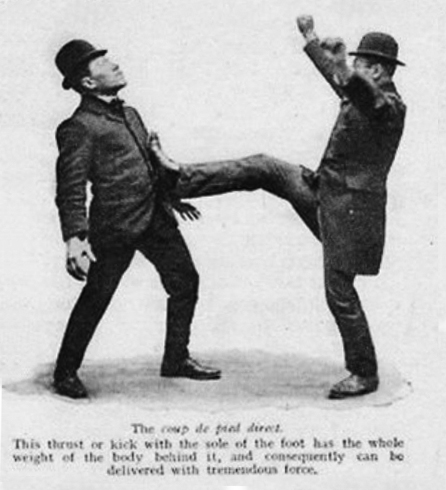

Coup de Pied Direct

Left leg and left arm in advance;

1. Shift the weight of the body forward onto the left leg.

2. Strike a swift jab forward, with the sole of the foot, full in the chest.

The whole weight of the body being behind this kick, the force is tremendous.

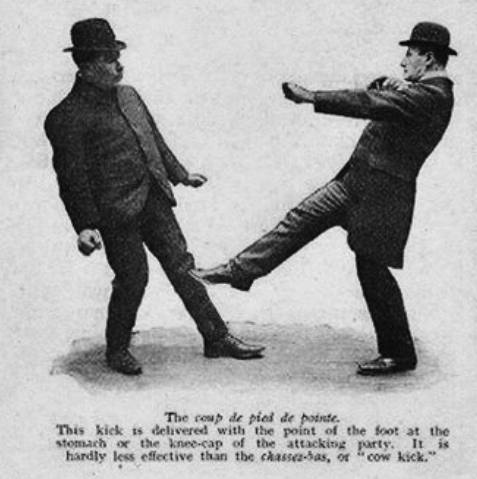

Coup de Pied de Pointe

Left leg and arm in front.

1) Carry the weight of the body lightly on the left leg.

2) Kick forward with the point of the right foot either at the knee-cap or in the stomach.

This kick should be given with a quick, sharp stroke, and the foot should at once be replaced behind the left one after delivery.

The best way to use this kick is to aim only at the kneecap, as one, well delivered, will knock out the strongest man with ease and quickness that is amazing.